Indiana Advocacy Blog

Legislative Process Overview

Structure

Indiana has a legislature made up of two houses, the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House of Representatives has 100 members governed by the Speaker of the House, and the Senate has 50 members governed by the Lieutenant Governor (much like the U.S. Senate’s president is the Vice President of the United States) and the President Pro Tempore.

Schedule

Indiana’s legislature is a part-time legislature which meets to make laws Monday through Thursday for only a few months of the year. The length of the legislative session switches back and forth between a long Session (in odd years) when the two-year budget is written, and a short Session (in even years) when the budget isn’t being drafted. Both Sessions begin in early January, but the long Session must end by April 29th and the short Session must end by March 14th.

Procedures

Legislators have all spring, summer, and fall to think about bills they might want to author during Session. Their ideas come from Interim Study Committees about policy topics, residents of their district (constituents), and stakeholder groups who are often represented by lobbyists. These ideas are submitted to the non-partisan Legislative Services Agency (LSA) for drafting in the fall.

As a general rule, all requests must be submitted by Thanksgiving, which means legislators are often bombarded with requests from late August onward. This can be a competitive process because legislators are limited in the number of bills they can author, with lower caps implemented during a short Session. By waiting until the last minute, a legislator’s slate of bills might already be full. In this case, the legislator might direct a late requestor to one of their colleagues, consider adding language from late requests into a related bill they are already authoring, or suggest trying to have the language added into a relevant bill later in the process as an amendment.

During late November and throughout December, LSA attorneys work long hours to draft the proposed legislation and run it through a process of fiscal analysis. Proposals that will cost the state above a set amount of money—usually around $150,000—will require scrutiny from a policy committee as well as a committee to consider its fiscal implications before they can proceed.

Session officially/ceremonially begins on Organization Day, which falls on the third Tuesday following the third Monday in November. (Practically speaking, this often means the Tuesday before Thanksgiving.) Newly-elected legislators are sworn in and bills are officially allowed to be filed. The window to file bills typically closes in early January.

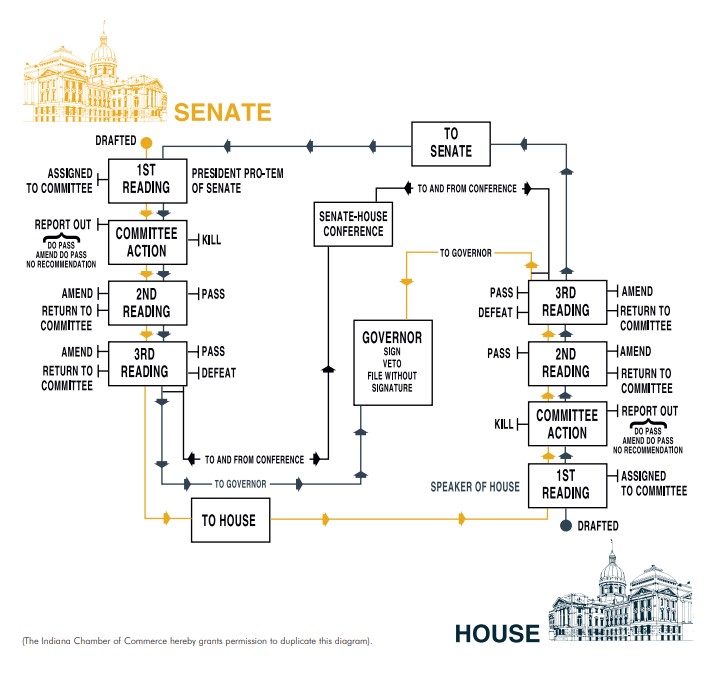

How a bill becomes a law

To become a law, a bill must make it through an arduous process. It will first be assigned to a policy committee in its house of origin in a process called First Reading. That committee’s chairman/chairwoman has ultimate decision-making power on whether to schedule the bill for consideration, amendment (if desired), and a vote. If it carries a large fiscal note, it must also be voted out of a fiscal committee. During Second Reading, the bill goes to the floor of the house of origin where all legislators—not just members of one committee—can offer amendments. This is followed by Third Reading, when legislators may go to the podium and speak in favor of or in opposition to the bill. Third Reading ends in a vote of the whole body. If there is a simple majority in favor, the bill moves on to the other house and the bill’s author will name sponsors to shepherd it through the same process in that chamber.

Just because bill passes on Third Reading in both houses doesn’t mean the process is over. If the same language passes in both houses, it goes to the Governor who can decide whether to sign it or not. If the language has been amended in the second house (it doesn’t match what the first house approved), it can trigger a Conference Committee. First, the bill’s author is given an opportunity to Concur to the changes. That Concurrence is placed on the calendar of the original house and everyone must vote again to approve. If the Concurrence fails or if the author doesn’t like the new version, the author can file a Dissent. In this case, four legislators—one from each house and each party—are assigned to a Conference Committee to hash out a version that they can all agree on. This process can be very contentious and often runs down to the last minute. All four must sign off on the compromise version, and then both chambers must hold votes to approve it. Either way, if a Concurrence or Conference Committee Report (the compromise version of the bill) passes, it still goes to the Governor for signature. In almost all cases, the Governor will sign the bill. However, if he does not, it can trigger a veto process where the chambers have an opportunity to override the Governor’s lack of approval in a 2/3 majority vote.

As a final complication, there are internal deadlines governing committee votes, and Second and Third Reading. This means that there are only a set amount of weeks for bills in committee to be heard. Anything that isn’t heard and voted out of committee by the deadline dies. The same goes for bills on Second and Third Reading. This splits Session into two halves with the intermission signaling the switch of bills to their second chamber. Conference committees are usually saved for the end of Session, typically the last two weeks before the mandated last day.